At the 241st Meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) in Seattle in January, many astronomers celebrated while getting down to work. The conference, one of the biggest for the field, was the first since the James Webb Space Telescope formally started science operations last July after completing six months of post-launch commissioning.

The celebrations came from the performance of JWST. After decades of development and anticipation — and plenty of worrying — project scientists confirmed that the space telescope was meeting, and often far exceeding, expectations.

“Basically, it’s nothing but good news,” said Jane Rigby, operations project scientist for JWST at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, in a speech that opened the conference Jan. 9. “It really is better than we expected across the board.” That ranges from the sensitivity of its instruments to JWST’s lifetime, now expected to be at least 20 years based on the amount of propellant on board.

The scientific fruits of those capabilities were on display at the conference as well, as astronomers discussed how they used JWST to study galaxies in the early universe and to confirm the discovery of an exoplanet. Astronomers attended a town hall session, once used to provide updates on the development of the observatory, to instead learn how to prepare proposals for the next round of JWST observations, called Cycle 2, that will begin this summer.

But even as astronomers took a “victory lap,” in the words of one NASA official, about JWST, some were looking beyond that space telescope. They hoped to capitalize on the success of, and enthusiasm surrounding, JWST to build support for a future line of large space telescopes and accelerate their development.

Introducing the Habitable Worlds Observatory

The latest astrophysics decadal survey, called Astro2020 and published in November 2021, recommended that NASA pursue development of a space telescope six meters across that operates in the ultraviolet, visible and near infrared. The telescope, with an estimated cost of $11 billion, would launch in the early 2040s.

Astro2020 came out as NASA and astronomers were focused on the impending launch of JWST. With that space telescope now in operation, they have turned their attention back to the decadal and the next steps in turning that concept into a mission.

One of the first steps was to give that telescope, unnamed in the decadal survey, a moniker. Last fall, NASA quietly started referring to that telescope as the “Habitable Worlds Observatory,” using the term in presentations and congressional testimony.

“We basically had to start using something because we’ve been having a lot of discussions with our stakeholders,” said Mark Clampin, who took over as director of NASA’s astrophysics division last August, during an agency town hall session at the AAS conference.

The designation — a working name for now — is intended to reflect the telescope’s mission to study potentially habitable exoplanets while also serving as a general-purpose observatory for astrophysics, he explained. (It was also, some astronomers noted, an improvement over the designation NASA has been using: IROUV, an acronym for infrared, optical and ultraviolet.)

Beyond the name, though, there are few details about the Habitable Worlds Observatory, including even a notional illustration of it. The telescope endorsed by Astro2020 was not one of the four concepts that NASA funded studies of; it instead falls between the larger LUVOIR telescope, whose primary mirror is between 8 and 16 meters across, and the smaller HabEx, four meters across.

However, Clampin offered a glimpse at the approach he planned to take for the observatory, offering a set of tenets to guide its development that he said would explain “how do we build it, and how do we convince people who are going to be our stakeholders and allow us to build it, that we know what we’re doing,” he said.

First and foremost, he said, was to build the telescope to a fixed schedule. NASA would set a launch date for the mission and make that a “Level 1” requirement alongside scientific ones, an approach he compared to planetary missions with limited launch windows. “We mature the technologies and then we set the schedule,” he said. Doing so, he argued, would help constrain its cost and allow NASA to move on to other flagship missions more quickly.

Tied to that was a second tenet was to evolve existing technologies and limit investment in brand-new ones that are far less mature. He cited as an example the segmented mirror design of JWST, which he suggested would likely be adopted for Habitable Worlds Observatory. A key instrument for the telescope will be a coronagraph that blocks starlight, allowing direct observations of exoplanets orbiting it; it will be based on one built for the Roman Space Telescope to be launched later this decade.

“It shows that we’re focused. It shows that we’re building on NASA investments,” he said.

A third tenet is that NASA will design the telescope to take advantage of the capabilities of new large launch vehicles. That could make it easier and less expensive to develop since it would not need to fold up as tightly to fit inside something like Starship or the Space Launch System.

“We would be insane not to use them,” he said. “Big fairings on big rockets give you flexibility. They allow you to not be constrained by mass or volume, both of which are big issues.” Even before the release of Astro2020, engineers studied how concepts like the bigger LUVOIR could fit inside Starship or SLS.

Clampin’s six tenets for the Habitable Worlds Observatory

| 1. Build to schedule | Set a launch date and make it a “Level 1” requirement alongside science requirements. |

| 2. Evolve technology | Evolve existing technologies and limit investments in brand-new ones. |

| 3. Next-generation rockets | Design the telescope to take advantage of large new launch vehicles like Starship and SLS to facilitate mass and volume trades. |

| 4. Planned servicing | Design it to be serviced by robots at the L2 Lagrange point |

| 5. Robust margins | Design it with large technical and scientific margins. |

| 6. Mature technologies first | Fully mature new technologies needed for the observatory before moving into development. |

A fourth tenet is to design Habitable Worlds Observatory to be serviced. “There’s a veritable gold rush of commercial companies looking to do robotic servicing,” Clampin said, that NASA can take advantage of.

That servicing would extend to upgrading the telescope’s instruments, allowing NASA to work around some of the schedule and technology challenges the mission faces. “We don’t necessarily have to hit all of the science goals the first time,” he said.

Having robust science margins was the fifth tenet that Clampin described, which he said addresses some of the uncertainty about achieving science goals. Among them is a figure called “eta Earth,” or the average number of Earth-sized planets in the habitable zone of a star, a key factor in determining how well the telescope can meet its goals of characterizing such planets.

Estimates of eta Earth vary widely, said Jessie Christiansen, an astronomer at Caltech, in a talk at the AAS conference. That affects the design of the telescope: the smaller eta Earth is, the fewer planets a telescope of a certain size would likely be able to study. “It would really be fabulous for a lot of people’s blood pressure to know this number a little bit better,” she said.

A flexible design for the Habitable Worlds Observatory, Clampin said, could also relieve that pressure. “Not locking ourselves into an aperture size too early is fundamental,” he said, another argument for using segmented mirrors that can be added or removed as needed in the design phase.

Mapping technology development

The final tenet that Clampin discussed at the town hall meeting was to fully mature new technologies needed for the observatory before moving into development. That was a recommendation from Astro2020, which called on NASA to establish a technology development program for both Habitable Worlds Observatory and future X-ray and far-infrared flagship telescopes.

NASA, in response, established a Great Observatories Mission and Technology Maturation Program, or GOMAP, last year. The first stage of the program, largely to set up the overall effort, has been completed, said Julie Crooke, GOMAP program executive at NASA Headquarters, during a side meeting at the AAS conference.

NASA is gearing up for the second stage of GOMAP, which will conduct a concept maturation study for Habitable Worlds Observatory. That will examine the various science, technology and architecture possibilities for the telescope. “We really want to look at the whole option space,” she said.

That study will be done by an independent team of 20 to 30 scientists and engineers, supported by independent consultants with expertise in cost modeling and scheduling. The study would begin later this year and run through September 2024.

The third stage of GOMAP, after the completion of the concept maturation study, is what NASA calls an “evolved pre-Phase A” study for Habitable Worlds Observatory. That will further refine the design of the telescope and mature key technologies needed for it so that formal work on the mission can start as soon as 2029.

NASA wants to move “as swiftly as possible” through the design and technology development work for the observatory, she said, but cautioned the timeline she presented was notional. “It’s dependent on the funding that NASA receives.”

Spreading the gospel of the New Great Observatories

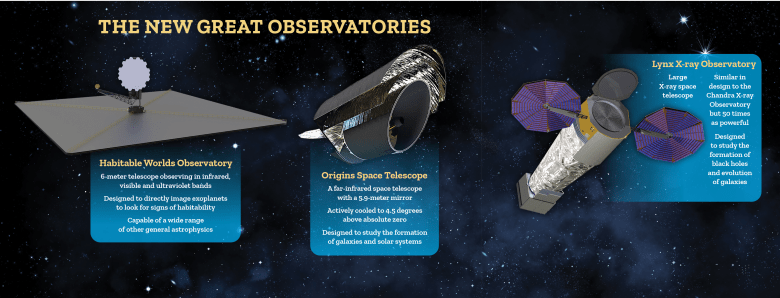

As GOMAP moves into that third stage, it will also look at the technologies needed for future flagships: the X-ray telescope based on a concept called the Lynx X-ray Observatory studied for Astro2020, and a far-infrared telescope based on another Astro2020 concept, the Origins Space Telescope.

“We’ll move forward as expeditiously as possible for the Habitable Worlds Observatory while also laying the groundwork for the other future great observatories,” Crooke promised.

Many astronomers have rallied behind a concept they call the New Great Observatories, which includes the Habitable Worlds Observatory and the later far-infrared and X-ray telescopes also endorsed by the decadal survey. They compare it to NASA’s original Great Observatories, which included the Hubble Space Telescope, Compton Gamma-Ray Observatory, Chandra X-Ray Observatory and Spitzer Space Telescope.

Just as the original Great Observatories worked mostly in parallel (Compton was deorbited a few years before Spitzer launched), astronomers want the three New Great Observatories in operation simultaneously, allowing them to work together to make breakthroughs in fields like searching for habitable exoplanets.

“The habitability of a given planet is impacted by the X-ray and far-ultraviolet spectrum and activity of its star,” said Christiansen. “The Habitable Worlds Observatory can only succeed in its mission if we also have contemporaneous X-ray and far-ultraviolet capabilities at the same time.”

She spoke at a workshop during the AAS conference where a standing-room-only crowd heard about the prospects of accelerating work on the New Great Observatories. A grassroots coalition sought to build support for speeding up work on the telescopes, something they acknowledged would require significant funding increases for NASA’s astrophysics programs.

Jason Tumlinson, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute, presented some funding profiles at the meeting. One profile would allow Habitable Worlds Observatory, costing $11 billion, to launch in 2041, with the X-ray and far-infrared telescopes to follow in 2047 and 2051. (The order of those two future missions is not important, most astronomers believe.) “This is what we want, but it’s not soon enough,” he said.

Even that assessment was optimistic to some. “If we take the decadal on its face, it’s worth noting the last of the Great Observatories will complete and launch in 2065,” estimated Jonathan Arenberg, chief mission architect for science robotic exploration at Northrop Grumman. “Needless to say, that’s too damn slow.”

An alternative budget profile offered by Tumlinson would allow Habitable Worlds Observatory to launch in 2035, with the other two following in 2040 and 2045. The catch? It assumes NASA’s astrophysics budget, currently about $1.5 billion a year, grows to $2.5 billion annually. “This is a budget that will execute a program that we all want, and it can be done,” he said, noting that increased budget is less than the current annual budget for planetary science at NASA.

Arenberg, who worked on Chandra and JWST, saw opportunities to make the design and construction of those telescopes more efficient. “Our current development paradigm could, at best, be described as pre-industrial or artisanal,” he said. He advocated for developing all three missions as a single program (and, presumably, with a single contractor), maximizing reuse of technology and personnel that could cut costs and reduce development times.

One organizer of the workshop was Grant Tremblay, an astronomer at the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and something of an evangelist for the New Great Observatories. At the start of the meeting, he outlined all the factors working against the concept, from constrained budgets and a renewed focus on human spaceflight to inflation and geopolitical instability. But, he argued, all those challenges also existed in the 1980s, when astronomers advocated and eventually won funding for the original Great Observatories.

He hopes that NASA’s recent successes, including with JWST, can build momentum for the New Great Observatories. “This has been one of the most triumphant two years in recent NASA history,” he said. What those successes had in common, he argued, were advocates who fought for their projects in good times and bad.

The New Great Observatories will need that same advocacy, he told the packed room. “This is three decades. We have a long road ahead of us,” he said. “We are not just pursuing one observatory. We’re pursuing a fleet, starting with the Habitable Worlds Observatory.”

This article originally appeared in the February 2023 issue of SpaceNews magazine.